Drop off your CV/Resume

We'd love to hear from you. Send us your CV/Resume and one of our team will be in touch.

Ever since the pandemic, mRNA vaccines seem to be the talk of the town due to their proven s...

Ever since the pandemic, mRNA vaccines seem to be the talk of the town due to their proven speed, safety, and ease. However, as those in the oncology sector will know, the technology has been around for decades, researched over and over, with the long-term goal of finding a successful cancer vaccine.

We’ve long known that our immune systems naturally try to fight cancer, but they’re often outsmarted, costing 10 million people their lives each year. You see, cancer is a deceitful disease – its cells start from our own healthy cells, meaning our bodies might not initially recognise cancer as harmful, so rather than attacking and destroying cancer cells, our immune systems ignore them, giving them time to grow and spread.

Cancer, or The Big C, is one of the deadliest diseases in the world and, in some capacity, is likely to impact all of us throughout our lifetimes. So, with World Cancer Day coming up tomorrow – February 4th – we wanted to share some insight into the progress in Life Sciences to come up with more effective treatments and, hopefully, in the long run, a cure.

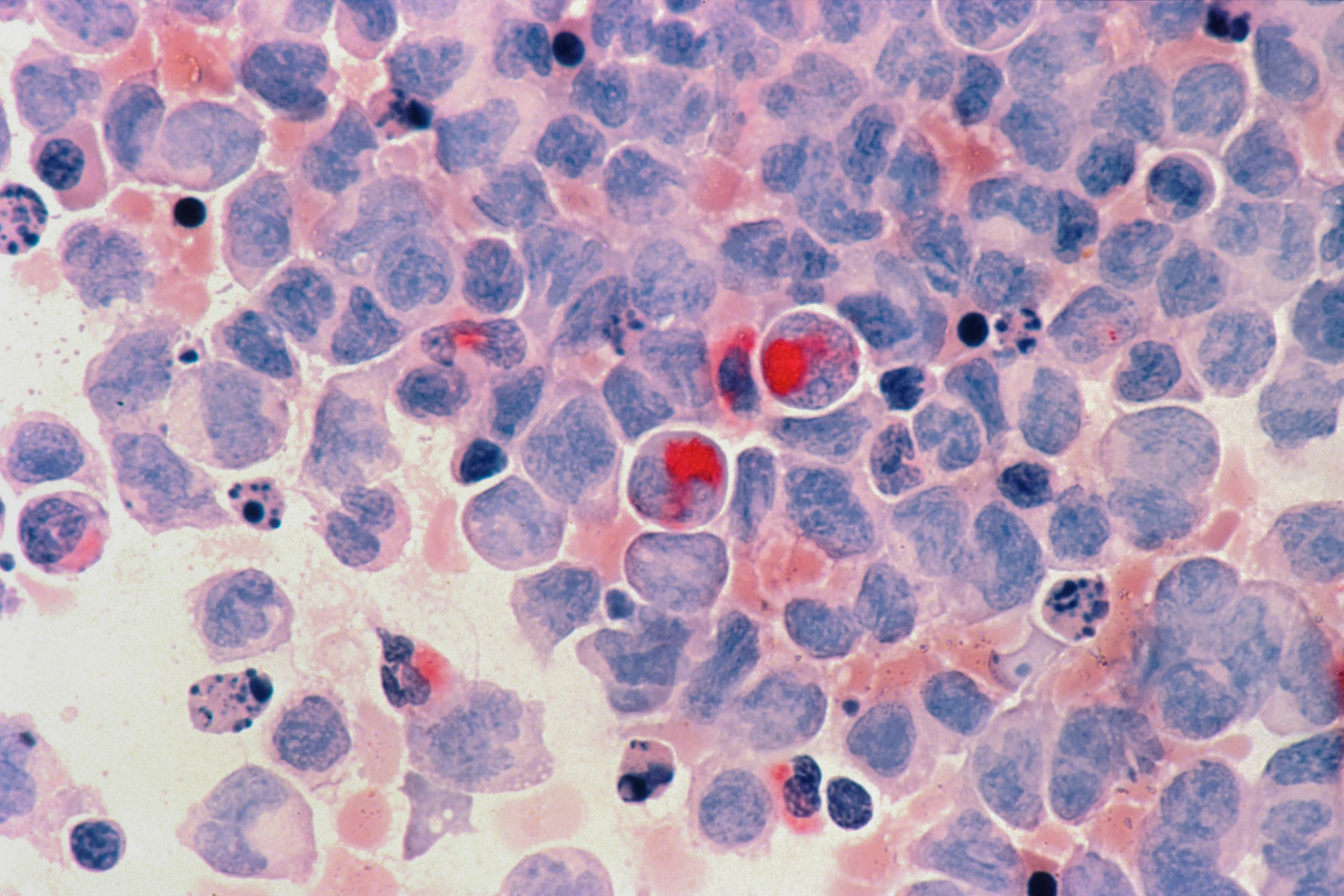

For all types of cancer apart from leukaemia (which affects our bloodstream), the disease occurs when a group of normal cells change within our bodies, leading to uncontrolled, abnormal growth that forms a tumour.

If the tumours are left untreated, they can spread into the surrounding tissue and other parts of the body by way of our bloodstream and lymphatic systems. As a result, our digestive, nervous, and circulatory systems can be affected, and hormones may be released that affect our body’s functions.

Typically, tumours are divided up into three groups – benign, malignant, or precancerous.

Benign tumours are classed as non-cancerous and are rarely life-threatening. They tend to grow pretty slowly without spreading to other parts of the body. Usually, they’re made up of cells similar to our normal healthy cells and only cause problems if they grow large and become uncomfortable or press on other organs, for example, a brain tumour.

Malignant tumours can grow quite quickly and can destroy the neighbouring tissue. Often, cells of malignant tumours break away from the primary tumour and spread to other parts of the body through a process known as metastasis. Once they invade healthy tissue at a new site, they continue to divide and grow. These secondary sites are known as metastases, and the condition is referred to as metastatic cancer.

Precancerous tumours, also known as premalignant tumours, involve abnormal cells that are prone to developing into cancer.

Altogether there are five main types of cancer, which tend to be classified according to the cell they start from.

In today’s world, cancer can be treated in several different ways. The type of cancer and its development determines what treatments a patient should receive.

And now, thanks to the promising results of numerous clinical trials, there’s a hopeful possibility that personalised cancer vaccines will be another leading therapy. So, let’s look into the tailormade vaccines in more detail…

Usually, cancer cells have certain molecules called cancer-specific antigens on their surface that are not apparent on our normal healthy cells. Personalised cancer vaccines are designed to boost our immune system’s ability to find and destroy cancer cells by feeding these molecules to a person. The molecules act as antigens that tell the immune system to kill cancer cells with the same molecules on their surface.

The reason why the vaccines are personalised is that we all have different DNA. That means that each patient’s DNA is analysed, usually through samples of their tumours, and then placed into a strain of mRNA which signals their immune systems to attack and destroy the unique biology of their tumours.

So, now we’re up to speed on what personalised vaccines do, let’s delve into a few clinical studies to find out how effective they are and how they could reshape the future of cancer therapy…

Back in October 2022, Moderna (who became a household name throughout the pandemic) announced they were joining forces with Merck to develop and commercialise a treatment known as mRNA-4157/V940, with the two both sharing costs and profits equally.

Fast forward to December, the two companies published the results of their clinical trials, which treated patients with their personalised cancer vaccine in conjunction with Merck’s immunotherapy drug, Keytruda. These results sent ripples throughout the world of cancer research.

Within the ongoing trial, all 157 patients had stage III/IV melanoma, meaning that the cancer had spread to their lymph nodes. Usually, in this instance, the course of action would be undergoing surgery to remove the tumours and the surrounding lymph nodes. Then the patients would receive infusions of an anti-PD-1 drug – typically Merck’s Keytruda.

With the aim of delaying disease recurrence, the trial saw that each patient’s tumours had been removed before being treated with either the drug/vaccine combination or Keytruda alone.

In order to create the individualised vaccines, scientists took the patients’ melanoma samples and decoded their genetic sequences. From there, they took the most mutated parts of the DNA and set them into a strand of mRNA, which was then injected into the patients.

Because we all have different DNA, each patient received a slightly different vaccine with up to 34 different mutations encoded into just one strand of mRNA. Once in their bloodstream, similarly to the COVID-19 vaccines, the mRNA produced a small level of cancer inside the patients. This triggered the patients’ cells to act as a manufacturing plant, creating copies of the mutations for the immune system to recognise and destroy.

Altogether, the results demonstrated that in comparison to the standard approach of surgery followed by anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, the personalised vaccine followed by Keytruda reduced the risk of the deadly skin cancer returning by an impressive 44%.

What makes these results even more promising is that this study is the very first to show that combining mRNA technology with a drug that accelerates immune response can, in fact, offer a better result for melanoma patients – and potentially other cancers too. With that in mind, both Moderna and Merck intend to study the same approach in other highly mutated cancers, such as lung, bladder, and breast cancer.

As you can probably guess, this enormous step forward in cancer research has driven up Moderna’s shares by 20%, along with other biotechs working on similar treatments. So, as we await Phase III of Moderna and Merck’s study to begin (predicted to happen later this year), the research area is only growing more traction with more trials geared towards more cancer types being developed.

If you’re unaware of who Genentech are, they’re a 40-year-old biotech business owned by Roche, who dished out an enormous $310 million to BioNTech to gain access to their renowned mRNA technology.

After the deal was complete, the collaboration resulted in what’s known as Autogene Cevumeran, a personalised vaccine targeting patients with melanoma, lung, breast, and colorectal cancer.

In June of last year, Phase I trials delivered the tailormade vaccines to 144 patients in conjunction with the immunotherapy drug, Tecentriq. The trial’s aim, like Moderna and Merck’s, was to treat the patients with the vaccine alongside immunotherapy to prompt an immune response to pinpoint and kill the patient’s cancer cells.

We should note here that prior to the trial, patients had already received several treatments, with 40% having had immunotherapy.

So, how did Genentech create their vaccines?

Researchers took blood and tumour samples from each patient and ran them through an algorithm. The algorithm detected parts of the tumour that the body would recognise as foreign, which then informed the creation of the individual vaccines.

Throughout the trial, patients received different doses of the vaccine, ranging from 15-50mg, once a week for six weeks – the seventh and eighth doses were administered fortnightly. In addition, all patients received Tencentriq on a 21-day cycle, with a booster dose of their vaccine during the 7th cycle of Tencentriq.

When it came to the analysis, the study’s results found that out of 63 of the patient’s blood samples, the immune system in 73% of the patients had been activated in response to the vaccines. Still, of the 108 patients who received a tumour assessment, only nine responded – that equates to an overall response rate of just 8%.

Although the overall clinical response rate was unfortunately low, researchers uncovered some valuable information for future research. Dr. Juanita Lopez, who presented the results at the American Association for Cancer Research conference, commented, “We were able to generate tumour-specific immune responses in the majority of evaluable patients, using a personalised cancer vaccine approach in combination with immune checkpoint blockade. It is likely our overall low clinical response rate is due to the advanced disease many patients had and the large number of treatments they had already received.”

Throughout the pandemic, BioNTech, famous for their mRNA vaccine technology, partnered with Pfizer to develop the world’s bestselling Covid jab, which has saved millions of people worldwide – and they have no plans for slowing down!

Since part-funding Genentech’s research last year, they’ve partnered with the UK to open a new R&D centre to fast-track the development of their mRNA vaccines over the next seven years while also expanding their reach in the UK.

For context, BioNTech has been developing mRNA-based cancer therapies since it was first founded in 2008, focusing on patients’ unique tumours. The very first person to receive a fully individualised mRNA-based cancer therapy developed by the company was treated in a clinical trial in 2014.

A year later, in 2015, an experimental mRNA-based cancer treatment was given to its first patient intravenously, with BioNTech pioneering the first intravenous nanoparticle delivery of mRNA vaccines in humans.

Up until now, several hundred patients have received mRNA-based cancer therapies through BioNTech’s clinical trials, and today, the company continues to evaluate various combinations of mRNA delivery.

So, in their 2023 partnership with the UK, the biotechnology company plans to utilise the country’s clinical trial network, unmatched genomics industry, and health data assets. They’ll recruit candidates and trial sites and set up their development plan – currently aiming to be up and running by the second half of this year.

To help the BioNTech team select candidates, the NHS and Genomics England have introduced the Cancer Vaccine Launch Pad – a platform that will help rapidly identify large numbers of cancer patients who could be eligible for the clinical trials, as well as explore potential vaccines across multiple types of cancer.

With trials set to start later this year, the ambition is to deliver personalised therapies to over 10,00 patients by 2030.

What we know so far is that the genetically-tailored vaccines will be aimed at helping patients with early and late-stage cancers, attaching to their immune systems to tackle their tumours. If the trials are successful, the personalised vaccines could become part of standard care in the UK and completely revolutionise the field overseas too.

Ugur Sahin, CEO and Co-founder of BioNTech, said of the partnership, “Our goal is to accelerate the development of immunotherapies and vaccines using technologies we’ve been researching for over 20 years. The collaboration [with the UK] will cover various cancer types and infectious diseases affecting hundreds of millions of people worldwide.”

After many failed attempts in the field, recent studies have demonstrated that personalised cancer vaccines are a promising research area.

Dr. Mary Lenora Disis, Director of the UW Medicine Cancer Vaccine Institute in Seattle, said, “In general, I think cancer vaccines are kind of at a tipping point, and there are going to probably be a lot of vaccines coming down the pipeline in the next five years.”

Norbert Pardi, Assistant Professor at the University of Pennsylvania, who’s seen trials where a vaccine has stimulated the patient’s immune system but has had little impact on the tumour (think Genentech’s study), comments, “I think the most important hurdle we need to overcome is why we don’t always see the benefit in patients even in the presence of a robust immune response.”

And BioNTech’s Ugur Sahin says, “The Covid-19 vaccine and our expertise in developing it has contributed to our work in oncology. We have learned how to better and faster manufacture vaccines, we have learned about how the immune system reacts to mRNA in a large number of people. And not only have we learned about mRNA vaccines and how to deal with them but also the regulators, so all this will support the acceleration of the development of mRNA-based cancer vaccines”.

Personalised cancer vaccines are undoubtedly a growing research sector, and we can only hope for more significant and transformative clinical trial results in the near future.

If you’re an oncology professional looking for a new and exciting career challenge, reach out to us.

Here at Meet, we pride ourselves on creating long-lasting relationships between Life Sciences businesses and professionals, and we’d be thrilled to help you find the next step in your career.